A beach town preserves its more civilized past. Carmel’s legacy lives on, a beacon for travelers.

by Donna Peck

Time and space expanded in surprising ways on a brief trip to Carmel. Below the surface of this postcard-pretty beach town, 120 miles south of San Francisco, is a hard-earned tale of endurance.

I stood at the balcony at Hofsas House. An overcast sky hung over Monterey Peninsula, folding the ocean into its solid gray mass. How may hours before I could discard the layers? I zipped my fleece jacket and went searching for coffee. In the hotel lobby, owner and city councilwoman Carrie Theis—already at work at 7 a.m.—came out from reception with a fresh cup of coffee, a map and a nod toward the center of town.

Along Ocean Avenue, pink roses trailed up thatched roofs and plush red geraniums spilled from flower boxes. In the sidewalk gardens, not a single dead bloom appeared among the petunias and snapdragons. I no longer bothered about the weather.

On a side street, an upstairs dining room extended into the canopy of a cypress pine. I silently thanked the city council for forcing new construction around existing trees. Ditto for banning chain restaurants. I didn’t pass a single Starbucks.

As the shops thinned out and the pine trees grew thicker, a sign appeared for the Forest Theater. Below the gate, a Greek amphitheater appeared with tiers of seats in a cavernous hollow.

This year “Beauty and the Beast,” and “Shakespeare in Love” are playing. Posters for the July Carmel Bach Festival list two weeks of concerts and recitals. Carmel’s ex-mayor, Clint Eastwood, often attends civic events: he led the centennial parade down Ocean Avenue in 2016.

I paused, taking in the town’s prodigious effort to continue the pursuit of nature, art and poetry.

The Carmel Legacy

In the early 1900s, artists shaped Carmel in their vision of an idyllic life. They erected art centers, outdoor theaters, playhouses—all in the Arts and Crafts aesthetic. They gave their stone houses and Tudor cottages names rather than street numbers.

At Carmel Beach, cold sea air stung my cheeks. A yellow-vested worker chatted with me, resting an arm on his backhoe before heading out to rake up the kelp. “High surf pounded the beach last night,” he said. He hopped into the cab, released the brake and rolled onto the sand.

I walked south on Carmel Beach, climbed a staircase and followed Scenic Road, just as the fog lifted and sunlight fell on Carmel River Estuary.

The poet Robinson Jeffers, arriving in 1918, built the first home at Carmel Point.

How beautiful when we first beheld it,

Unbroken field of poppy and lupine walled with clean cliffs;

No intrusion but two or three horses pasturing,

Or a few milch cows rubbing their flanks on the outcrop rock-heads—

He would be happy to see that the Carmel River once again has a functioning tidal marsh. Though it’s ringed by houses, (he’d hate that) hawks are hunting in the bulrushes.

The following afternoon I hiked Point Lobos with a docent and a dozen other visitors. The wildflowers caused an outburst of oohs and ahhs: fairy lanterns, seaside painted cups were among a record forty species blooming in the meadows.

Staircases wound up alongside rock gardens chock-full of stonecrops and descended to coves so thick with pebbles the ebb and flow of the tide made a sizzling sound.

Edward Weston moved to Carmel in 1929 and photographed Point Lobos, following in the footsteps of Arnold Genthe, who wrote that “the cypresses and rocks of Point Lobos, the always varying sunsets and the intriguing shadows of sand dunes” inspired his color photography.

In the cypress groves our docent, a retired medical researcher, pointed out the cypress tree that Ansel Adams photographed. Adams moved to Carmel Highlands in 1962 and joined the Carmel arts colony.

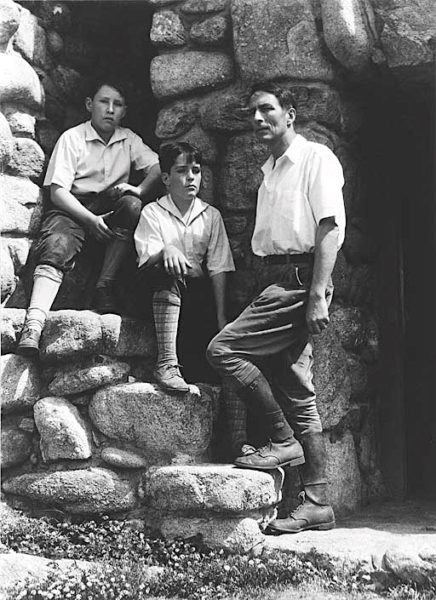

The next afternoon I visited Robinson Jeffers’ Tor House and Hawk Tower. When Jeffers began work on Hawk Tower in 1920 next to the house, rolling granite boulders from Carmel Bay’s rocky shore and placing one atop the other, a hawk often perched on a stone wall and watched him.

The tour guide wouldn’t let me take a photo inside Hawk Tower but I was surprised when she said, “Does anyone want to sit in the poet’s chair?” Jeffers wrote all his poetical works: the long narratives, the shorter meditative lyrics and dramas on classical themes, the 1947 Broadway adaptation of “Medea” with Dame Judith Anderson in the title role, while sitting in this chair.

I eased onto the dark-stained oak banker’s chair and glanced up at the golden glass eyes of a hawk perched on a shelf. Jeffers’ twin sons found the taxidermied bird with outspread wings in a thrift shop and bought it as a gift for their father. Halfway up the narrow staircase, I looked out the portholes that Jeffers installed for his boys. What a place to play pirates!

The top of the tower belonged to Una. Jeffers’ wife held seances and had a reputation among the neighbors as a psychic. She used a human skull in her seances. She picked up the handmade ethos and sewed four ‘poet’ shirts for Jeffers a year that he wore open without a tie.

His stone cottage and tower stand at the edge of the ocean, nothing impedes the view nor the sight of hawks, pelicans and seagulls. The view from the parapet also takes in the surrounding suburban development that Jeffers lamented in “Carmel Point.”

Jeffers bought four lots but sold them when it was time to send the boys to college. Imagine raising a family on a poet’s salary! Jeffers planted 2,000 cypress trees to preserve his privacy. I was silently grateful he did. His granite house and tower don’t show the passage of time. Not like the mid-century modern houses whose low-slung roofs, massive windows and projecting decks suffer in the winter storms.

….people are a tide

That swells and in time will ebb, and all

Their works dissolve. Meanwhile the image of the pristine beauty

Lives in the very grain of the granite,

Safe as the endless ocean that climbs our cliff.

Jeffers was fond of telling visitors that he would die in the corner bedroom facing the ocean. He did just that in 1962 at age 75. Maybe under the blanket woven from the yarn spun from wool on Una’s mother’s spinning wheel that sits in the living room.

Hearing his story, sitting at his desk, climbing his tower, standing at his death bed, I felt a whoosh of a life that seemed mythic, the stuff of legend. Successive generations may feel it, too, and be moved to join the effort in preserving Jeffers’ house and tower as well as Carmel’s Tudor cottages, Point Lobos Reserve, and the Carmel River Estuary.

I hadn’t come to Carmel at the beck and call of nature, art and poetry but what powerful forces of connection! Life is gone in a whoosh but the days can be long and leisurely if given over to civilized pursuits.

–photography by Donna Peck and VisitCarmel.

Donna Peck loves rolling down Pacific Coast Highway, on the lookout for hidden treasure in California’s beach towns.

Leave a Reply